It seems apparent that the ambitions of man have always had

a striking tendency to probe beyond the extent of standard physical and cognitive

capabilities. These desires are manifested and entrenched within the oldest of

mythologies and woven within the most novel fantasies. Among these is the

seemingly age-old vision of flight. In the West, this notion can be seen

manifest in the continuity of Greek thought, through the Medieval Catholic

world. It prominently captures ours and the imaginations of scholars, writers

and thinkers as an arrogant, romantic and inexorable dream. One such attempt

and focus on human aviation can be perceived strikingly obtrusively among the eclectic

and extensively rich history at Malmesbury Abbey.

In the year 1010 AD the

monk Eilmer of Malmesbury (Also known as Oliver or Elmer) attempted one of the

earliest recorded instances of flight from the top of Malmesbury Abbey tower. Eilmer,

in the tradition of rediscovering knowledge held by the ancient Greeks (alongside

others in academic circles of the time) began to observe of the natural world;

particularly creatures of the air. In study of bird-life he became captivated

by the concept of flight and envisaged this ability possible for humans.

Concluding from his avian examinations that he would attach wings to his arms,

utilising both wind and gravity he successfully flew over 200 meters only to crash-land

in Oliver’s Lane, breaking his legs and crippling him for the rest of his long

life. Also Eilmer had a strong familiarity with the tale of Daedalus and Icarus

of Greek myth and subsequently drew influence from this – It was thought he

‘might fly as Daedalus’[1].

Moreover, it is said he witnessed the passage of Halley’s Comet. The sight of a

heavenly body (of which little beyond religious context was known) may have

aided in prompting this endeavour. As a case study we can perceive in Eilmer a

certain fascination with ‘The Above’ when we consider also his work on

astrology. He later claimed his failure was simply due to the absence of a tail

to guide his course, even planned a second flight in determination of this.

Here we stumble upon

broader themes, notably a distinct attempt at revival and continuation of Greek

thought, culture and ideas, particularly among academic culture - not isolated

to this one event in Malmesbury. Indeed, various clergy would identify with doctrine

of dominion over animals demanded in Genesis (typifying an ideal of human

self-importance, righteous command over animals and provoking a notion that beasts

should have no feat over divine man). It would seem this notion of pushing man

to the limit of his dreams and aspirations overpowers the more seldom-found

pious humility which would deem flight a sinful desire, upsetting the natural

order by succeeding the God-given physical restrictions we possess. Many would

dabble with ideas of flight, such as Giovanni Damiani in Galloway, 1507, emanating

the mythical Daedalus - attempting flight with feathers alone. The conclusion

of this brave and foolhardy endeavour is evident of course… he was not

successful. We see further wishes and attempts of flight in the Middle East,

the designs of Da Vinci and even Ancient China. In Eilmer’s ‘epic flight’[2],

we see some degree of scientific method alongside a driven faith and awe;

observation, aerodynamic design, logical positioning and post-flight analysis -

rather than daring a fairy tale unarmed.

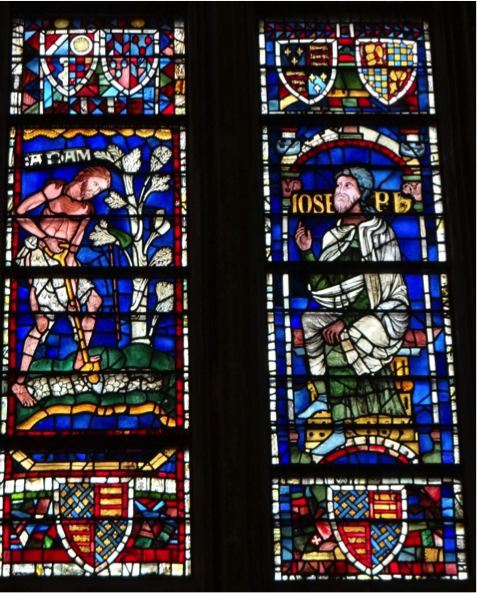

It is striking that Eilmer is remembered and revered so when

the other achievements of the Abbey throughout its history were comparatively

great; surviving the dissolution and holding the first organ and largest

library in England and being the resting place of King Æthelstan. Yet William

of Malmesbury, heralded with ‘justice to be the greatest medieval monastic

historian’[3]

chose to write extensively of Eilmer. Furthermore, Eilmer was hardly a Wright

brother and it was not his only accomplishment, with his work at the abbey

including having produced several astrological treatises which remained in

circulation until the 16th Century. Even the abbey focuses on him to

commercial and historiographical effect; including him at the forefront of

historical summaries, art, celebration, even re-enactment, not to mention

revering the ‘hero’[4] by

depiction on the stain glass windows of its north side, holding a place among

abbots, commanders, saints and messiahs. Perhaps his idolisation owes to his

bold facing of the perils and dangers during his attempt, seemingly unfased by

the foreshadowed warning inherent in myth of Daedalus of man flying too close

to the sun.

Connor Bevan is a second-year RPE student. This is a reflection piece written after a visit to Malmesbury Abbey during the Philosophytown festival on 10th October 2014.

Bibliography:

Bartholomew, Ron, A

History of Malmesbury Abbey, (Malmesbury: Friends of Malmesbury Abbey,

2010)

http://www.malmesburyabbey.com/ (14/10/2014)

Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition, White, Lynn, Jr., Technology and Culture, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring, 1961), pp. 97-111 (http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3101411?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21104815674567)

http://www.athelstanmuseum.org.uk/people_eilmer.html (14/10/2014)

Willis, Roy, World Mythology, (London: Duncan Baird Publishers Ltd, 2006)

Cotterell, Arthur, The Encyclopaedia Mythology, (Surrey, Anness Publishing Limited, 1996)

Knowles, Dom David, The Monastic Order in England: A History of Its Development from the Times of St Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council 940-1216, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

William of Malmesbury, Allen Giles, John, William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the kings of England. From the earliest period to the reign of King Stephen (H.G. Bohn, 1847)(Reprinted Blackwell: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2004)pg. 252

http://www.malmesburyabbey.com/ (14/10/2014)

Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition, White, Lynn, Jr., Technology and Culture, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring, 1961), pp. 97-111 (http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3101411?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21104815674567)

http://www.athelstanmuseum.org.uk/people_eilmer.html (14/10/2014)

Willis, Roy, World Mythology, (London: Duncan Baird Publishers Ltd, 2006)

Cotterell, Arthur, The Encyclopaedia Mythology, (Surrey, Anness Publishing Limited, 1996)

Knowles, Dom David, The Monastic Order in England: A History of Its Development from the Times of St Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council 940-1216, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

William of Malmesbury, Allen Giles, John, William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the kings of England. From the earliest period to the reign of King Stephen (H.G. Bohn, 1847)(Reprinted Blackwell: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2004)pg. 252

[1] William

of Malmesbury, Allen Giles, John, William

of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the kings of England. From the earliest period to

the reign of King Stephen (H.G. Bohn, 1847)(Reprinted Blackwell: Wipf and

Stock Publishers, 2004)pg. 252

[2]

Bartholomew, Ron, A History of Malmesbury

Abbey, (Malmesbury: Friends of Malmesbury Abbey, 2010) pg. 69

[3] Knowles,

Dom David, The Monastic Order in England:

A History of Its Development from the Times of St Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran

Council 940-1216, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) pg. 499

[4] A History of Malmesbury Abbey pg. 70